Students and faculty model the importance of working together across disciplines.

The wide field of natural science is a complex ecosystem. Just like a natural ecosystem, the different scientific disciplines cannot exist without each other. Scientists all depend on each other’s expertise to accomplish greater goals in science together.

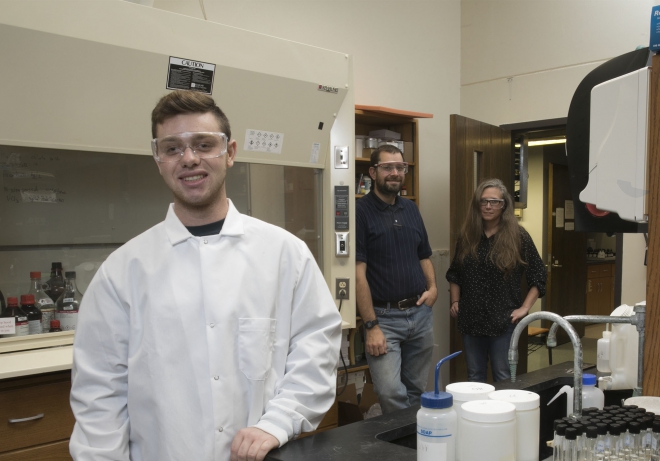

This is something science students learn firsthand every day at Ohio Northern University. Dr. Chris Spiese, associate professor of chemistry, and Dr. Kat Krynak, assistant professor of biology, have been a great example.

A few years ago, Spiese began working as the lead researcher on a grant-funded project hoping to fix the algal-bloom problem plaguing several inland lakes, an issue caused by nutrient runoff from nearby agriculture. The idea of the research is to apply different treatments to demonstration farm sites in Hardin County and observe the results by studying the effects on the surrounding ditches and waterways, such as the Blanchard River.

A few years ago, Spiese began working as the lead researcher on a grant-funded project hoping to fix the algal-bloom problem plaguing several inland lakes, an issue caused by nutrient runoff from nearby agriculture. The idea of the research is to apply different treatments to demonstration farm sites in Hardin County and observe the results by studying the effects on the surrounding ditches and waterways, such as the Blanchard River.

Spiese enlisted the help of then-sophomore Justin Kindle, a chemistry major from De Graff, Ohio, to work as an on-campus intern for the project. Kindle was drawn to pursuing this opportunity as a way of gaining practical experience in the lab, but what he took away from it was much loftier.

Kindle’s research was multidimensional, as he studied aspects of both chemistry and biology. This overlap in subject matter included working in Krynak’s lab, as well as Spiese’s, for a portion of the internship.

For the first four weeks, Kindle worked exclusively with Spiese studying the chemistry of the affected local waterways. For the next four weeks, he added a second dimension to the project by studying DNA extracts of microorganisms that are symbiotic with pill bugs at the test sites.

Kindle spent hours poring over DNA extracts in Krynak’s lab. Although Krynak wasn’t directly involved in the research herself, she took an interest in the work Kindle was doing, in respect to her scientific focus on microbial organisms and wildlife.

Kindle spent hours poring over DNA extracts in Krynak’s lab. Although Krynak wasn’t directly involved in the research herself, she took an interest in the work Kindle was doing, in respect to her scientific focus on microbial organisms and wildlife.

It was through Kindle that Krynak and Spiese, two faculty members in different scientific disciplines, became connected. They communicated about the project and Kindle’s involvement, ultimately coming to appreciate each other’s disciplines in contrast to their own scientific specialty.

For Krynak, it was a fascinating experience.

“It was great to hear about what Justin was learning in these other disciplines and ask him questions,” says Krynak. “I think that’s really good for a student’s confidence, and it’s just great to learn from the students as well. This is not my discipline. That aspect of it has been fantastic, and getting to know the faculty members in another department has been really helpful for me.”

It turns out that this subtle collaboration has served as a great real-life lesson to Kindle on the importance of collaboration in scientific research.

It was really cool to see the collaboration,” says Kindle. “From one aspect, Dr. Spiese was all about studying the chemistry of everything going on in the water, and Dr. Krynak was all about the biology of organisms within the ditches and waterways. So they both complemented each other in their own unique ways.

Collaboration is often the catalyst when it comes to making scientific discoveries. It is, in essence, the centerpiece that holds everything together.

Collaboration is often the catalyst when it comes to making scientific discoveries. It is, in essence, the centerpiece that holds everything together.

"We’re at a point in science where one discipline can’t do it by itself, especially in the environmental sciences,” says Spiese. “For me, I personally have a very specialized set of skills, so I need people outside of my discipline to help out."

It’s a great example reinforced not only by Spiese and Krynak, but also several other faculty members and students. Also involved in the project are biology professors Dr. Leslie Riley, Dr. Robert Verb and Dr. Ken Oswald, who have sampled fish, invertebrates and algae living in the ditches, and civil engineering professor Dr. David Johnstone, who has modeled flow in ditches to determine if the treatments can be used to mitigate flood events. Several students from both the biology and chemistry departments have also assisted in sampling and extensive field study. For the past two years, it’s been a huge undertaking with many players, connecting a large body of collaborators with the same goal.

Especially in environmental science, it takes all of us to answer these questions,” says Krynak. “Through projects like these, students see and understand the importance of the ability to communicate across disciplines and work with a variety of different people.

With still more research to be done, the group hopes to discover some solutions to the algal-bloom problem. Maybe answers will come sooner rather than later, and maybe it will take more digging. Nonetheless, all who are involved have come to find true allies in one another.