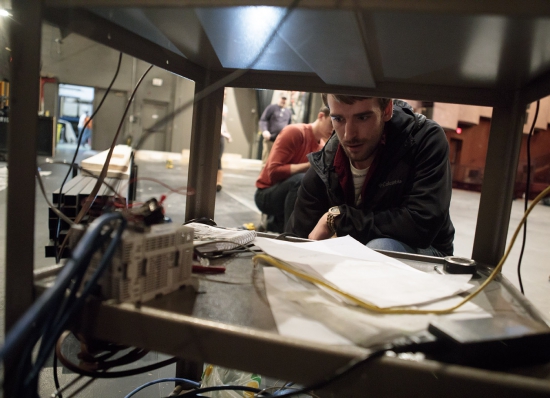

Above: Brian Phillips, technical director of the Freed Center for the Performing Arts, works with mechanical engineering majors Bella Balzano and Josh Woods.

Interdisciplinary capstone project to enhance Freed Center productions

In the real world, an engineering project is not cut and dried. Not everything is straightforward, the client’s needs are first and foremost, and timelines are often dynamic. It’s a whole different feel than completing an assignment on a syllabus.

That’s why Ohio Northern University’s T.J. Smull College of Engineering invests so deeply in its senior capstone projects. Unlike any other undergraduate project, the yearlong capstone course gives students a chance to implement the technical and nontechnical skills they have learned in order to solve real problems for real clients. The students themselves manage the entire project, tackling the entire process from start to finish – research, calculations, assembly, testing and product finalization.

Recent engineering graduates Bella Balzano, BSME ’18, Justin Sparks, BSEE ’18, Jared Emerson, BSEE ’18, Kevin Henderson, BSME ’18, and Josh Woods, BSME ’18, know this process all too well. The goal of their capstone project, “Interdisciplinary Stage-Automation Capstone,” was to create a stage-automation system that would enhance productions in the Freed Center for the Performing Arts. The system consistently and accurately moves heavy scenery across the stage while maintaining industry safety standards and providing extreme cost savings. (Purchasing a professional stage-automation system at retail price would cost several thousand dollars.)

Recent engineering graduates Bella Balzano, BSME ’18, Justin Sparks, BSEE ’18, Jared Emerson, BSEE ’18, Kevin Henderson, BSME ’18, and Josh Woods, BSME ’18, know this process all too well. The goal of their capstone project, “Interdisciplinary Stage-Automation Capstone,” was to create a stage-automation system that would enhance productions in the Freed Center for the Performing Arts. The system consistently and accurately moves heavy scenery across the stage while maintaining industry safety standards and providing extreme cost savings. (Purchasing a professional stage-automation system at retail price would cost several thousand dollars.)

The project was sponsored by Brian Phillips, technical director of the Freed Center.

Automated scenery is present at every level of theatrical production these days, and I wanted to give our students a chance to create with this technology,” says Phillips. “Stage automation is only getting bigger and more advanced, and people with both engineering and theatrical backgrounds are highly sought after.

Looking back now, the project was successful, and there are plans to use the system in the upcoming production of Romeo and Juliet during fall semester 2018. But when this project first began, these students were novices when it came to stage automation.

“Going into this project, the group knew very little of stage automation,” Balzano says in regard to the project’s early stages in fall 2017. “We had to start from the very beginning by conducting a lot of research about scenic movement systems to gain an understanding of the subject. From this point of knowing very little, we had to grow as a group to understand what electrical and mechanical components are required, how to program the system from scratch, and teach users to operate the system through the use of a manual we created.”

Once the initial research was behind them, it was on to the calculations and theory. They had a general end goal to work toward, but how they went about it was totally up to them. They had to not only come up with the right answers to their questions, but also formulate the correct questions to answer.

Of course, things really started to “get real” when the team was faced with exporting their work from the theoretical into reality. Upon their return from winter break, Woods recalls the moment of truth he experienced as the group started assembling their project.

“There was that really surreal moment the first time we walked in,” he says. “All the materials and parts were there, and it was neat to see it all in front of you, all of a sudden. It was no longer the theoretical ‘let’s do some calculations on a sheet of paper and hope it works and get the right answer.’ Now, it was about actually putting it together.”

It was at this point that the going really got tough. Not everything went as planned. Calculations didn’t always add up, some parts didn’t quite fit, design had to be adjusted. It was a long, sometimes frustrating process, but that made for the best possible learning environment for the students to gain the most real-world experience. Of course, they could always turn to their faculty advisors for help if need be.

It was at this point that the going really got tough. Not everything went as planned. Calculations didn’t always add up, some parts didn’t quite fit, design had to be adjusted. It was a long, sometimes frustrating process, but that made for the best possible learning environment for the students to gain the most real-world experience. Of course, they could always turn to their faculty advisors for help if need be.

Although the math and science were certainly central to the project’s success, communication and project management were just as important to keep the project on track and focused. The students worked closely with Phillips, their client, throughout the year, keeping him informed on the progress and making sure the result would fit his needs. This client communication piece was one of the most intense and most meaningful aspects of the project for the students.

“It was an incredible motivator to have a real client to work with, for a few reasons,” says Woods. “The first is that we, of course, did not want to disappoint the client. Part of the reason he approached the engineering college is because he believed we could help solve his problem, so we wanted to do just that. It also added an additional layer of difficulty because we had to balance the flow of information between our team, our advisors who were trying to help and our client who had his own unique experiences.”

That said, the team also had to learn to communicate well among themselves. This was especially important for this capstone project because the team divided the project into two sub-teams, one completing the mechanical components and the other the electrical elements and computer interface used to control the system. Learning how to keep everyone on the same page and combine everyone’s individual strengths resulted in incredible professional growth.

“These aspects of team-building are all present in the professional workplace, and I have seen them during my internship and co-op experiences,” Balzano says. “The team-building skills for this project have helped greater develop my skills and will be applicable in my career post-graduation.”

“These aspects of team-building are all present in the professional workplace, and I have seen them during my internship and co-op experiences,” Balzano says. “The team-building skills for this project have helped greater develop my skills and will be applicable in my career post-graduation.”

The defining factor of the capstone project is the fact that the students are the project managers in every sense. They are in charge of developing the goals, setting milestones, troubleshooting and keeping it all organized.

This project was unique because of how much of the decision-making rested on our shoulders,” Woods says. “Often for other projects, it feels like the work is a lot more guided or rigid due to a rubric or more fixed outcome. For capstone, we had an end goal but had to decide ourselves how to reach it.

For an aspiring engineer to have this kind of high-impact experience while still a student is rare and invaluable. It shows them just how many moving parts there are, literally and figuratively, in any given project – quite fitting, considering that’s what engineers love most.